The morning began like any other in the quiet suburb, the sun rising reluctantly. Brenda Ann Spencer, a 16-year-old girl with flaming red hair and haunted blue eyes, woke up in her small room. The gun leaned against the wall, a stark reminder of a gift from her father — a gift that spoke more of neglect and misunderstanding than affection. The same gun that, in just a few short hours, would carve her name into infamy.

The morning began like any other in the quiet suburb, the sun rising reluctantly. Brenda Ann Spencer, a 16-year-old girl with flaming red hair and haunted blue eyes, woke up in her small room. The gun leaned against the wall, a stark reminder of a gift from her father — a gift that spoke more of neglect and misunderstanding than affection. The same gun that, in just a few short hours, would carve her name into infamy.

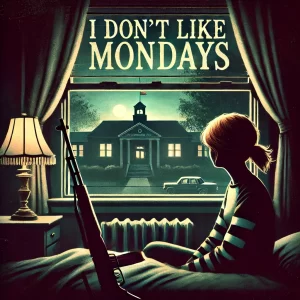

Brenda shuffled to the window, her hands trembling. Her father was already up, and she could hear his movements through the thin walls. The world outside seemed too bright, too indifferent. She looked across the street at Cleveland Elementary School. It was still quiet, not yet filled with the innocent shouts and laughter of children who had not yet learned to dread Mondays.

Her head throbbed with the remnants of last night’s argument — another in a long line of clashes with her father, a man who understood her as little as she understood herself. Her life was a sequence of Mondays, endless and unchanging, filled with the same hollow ache. In her mind, the thought formed again, a thought that had been echoing louder and louder: “I don’t like Mondays.”

It wasn’t just the day she hated. It was what it represented — a resumption of everything she loathed: the loneliness, the feeling of being invisible, the crushing weight of a life that felt like it was already over before it had even begun. She was tired of it. Tired of the indifference, the sneers, the alienation. She wanted to make a mark, to make the world stop for just a moment and notice that she existed.

The rifle was cold in her hands. She moved almost mechanically, pushing open the window, her eyes never leaving the playground. It felt strangely surreal, as if she were watching herself from a distance, a spectator in her own life. “I don’t like Mondays,” she whispered again, and this time, it felt like a resolution.

At 8:30 a.m., as the first children arrived at the school, Brenda took aim. The shots rang out like cracks in the morning calm, tearing through the air, tearing through lives. When it was over, two adults lay dead — the principal and a custodian who had tried to shield the children — and eight children and a police officer were wounded. The police surrounded her home, and when the call came asking why she did it, her response was chilling in its simplicity: “I don’t like Mondays. This livens up the day.”

Bob Geldof, the Irish singer and frontman of The Boomtown Rats, was in the United States when he learned of the shooting. He was struck by the senselessness, the sheer nihilism of Brenda’s answer. “I don’t like Mondays.”

Geldof called it the “perfect senseless act” with the “perfect senseless reason.”

The Boomtown Rats had just returned from their American tour, their heads still spinning from the whirlwind of shows, press conferences, and long bus rides. The band was exhausted, but there was an energy among them — a restlessness, a need to translate all they had seen and felt into something meaningful. Brenda Ann Spencer’s words, “I don’t like Mondays,” had lodged themselves in Geldof’s mind like a splinter.

Johnnie Fingers, the band’s keyboardist, came up with the initial piano riff. Inspired, Geldof began writing the lyrics on the spot. He was particularly struck by the nonchalant statement by Brenda Ann Spencer: “I don’t like Mondays. This livens up the day.” He used this disturbing phrase to build the song’s narrative, while Fingers continued to play the riff.

Phil Wainman wasn’t the band’s first choice to produce “I Don’t Like Mondays.” Known for his work with glam rock bands like Sweet, producing The Ballroom Blitz, Wainman was more associated with explosive, anthemic hits than the nuanced blend of irony and melancholy that “I Don’t Like Mondays” required. But the band’s management thought Wainman could bring a radio-friendly edge to their rebellious sound.

They chose to record at Trident Studios, located in the heart of London’s bustling Soho district. Trident was a modest building from the outside, almost easy to miss among the maze of narrow streets and lively nightlife. But inside, it was a hub of innovation and creativity. Trident’s cutting-edge recording technology was matched only by its warm, intimate acoustics. After all, this was where Bowie recorded “Space Oddity,” and where Queen layered the operatic harmonies of “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

The band gathered in the studio, surrounded by vintage Neumann microphones, stacks of Marshall amplifiers, and an imposing Steinway piano in the center of the room. Wainman decided to record the basic track live, with everyone playing together, to capture the immediacy of the emotion.

Geldof wanted the song to have a somber, almost dirge-like quality, while Wainman felt it needed a punchier, more dynamic sound to ensure it stood out on the radio. There were heated debates between Geldof and Wainman, with Geldof arguing for a minimalist approach and Wainman countering that they needed layers. “This isn’t just a newspaper headline,” he insisted. “It needs to feel like a living story,” .

Johnnie Fingers sat at the piano, his hands hovering over the keys, ready to play the riff that had set this whole thing in motion. As he struck the first notes, there was a chill in the air — a feeling that something heavy was hanging over them.

Wainman decided to experiment with the arrangement. He brought in additional musicians to add subtle string sections and even contemplated a choir to give the chorus a haunting quality. But after several hours, he scrapped the choir, realizing that the song’s strength lay in its simplicity. Instead, he focused on getting the perfect piano tone. He miked the piano from several angles, blending close-miked and ambient sounds to achieve a balance that was at once intimate and expansive.

Midway through the mixing session, an electrical issue, affecting only the lights, caused them to briefly black out. The band took a break while Wainman stayed in the control room, playing with the levels and adjusting the the EQ on the mixing board by candlelight. The blackout turned into an unexpected creative moment. When the lights flickered back on, Geldof, returning to the studio, found Wainman hunched over the console, his face illuminated by the soft glow of the VU meters.

He played the track, and the room fell silent. The piano riff was even more haunting, everything was crisper. It felt like the song had found its true form. “I think we’ve got it,” Wainman murmured, almost to himself.

“I Don’t Like Mondays was released on Ensign Records in July 1979, and almost immediately, it struck a nerve. It climbed to number one on the UK Singles Chart, and in over thirty countries worldwide. The American radio stations were hesitant though, most refused to play it. It was too soon, too raw. But the controversy only fueled its popularity.

For Brenda Ann Spencer, there was no such rise to fame. Convicted of two counts of murder and several counts of attempted murder, she was sentenced to 25 years to life in prison. She became an inmate at the California Institution for Women in Chino, a name in a forgotten file, occasionally surfacing in parole hearings, but never released. She told stories of abuse and addiction, offered explanations, sought to reclaim some understanding, but the world had already moved on.

Now, decades later, “I Don’t Like Mondays” remains a haunting reminder of that fateful day. Brenda’s crime, and the song it inspired, both linger in public memory, forever intertwined — a single act of violence frozen in time and a melody that asks, again and again, why?

In the end, there are no answers — just the echo of a gunshot, the refrain of a song, and a Monday morning that refused to be ordinary.