It is said that music, like fate, reveals itself in waves—at times crashing in violent upheaval, at times receding into quiet memory. Van Halen, this band of jesters and alchemists, did not just play rock ‘n roll, they embodied a reckless, divine laughter.

It is said that music, like fate, reveals itself in waves—at times crashing in violent upheaval, at times receding into quiet memory. Van Halen, this band of jesters and alchemists, did not just play rock ‘n roll, they embodied a reckless, divine laughter.

Their first six albums are an unchained rebellion against the void. And so, in the spirit of inquiry and self-reflection, let us examine these works in order of importance.

I. Van Halen (1978)

It begins as all revelations do: with a single, devastating truth. In this case, it is Eruption, a sound so unearthly, so violent in its execution, that it is less a song and more a vision—a man staring into the face of God. Eddie Van Halen’s playing is a force climbing skyward—each phrase fighting against gravity, demanding effort, energy, and belief. It’s an affront to the established order of rock, a thing that should not be.

Yet it does not end there. Van Halen as a whole is not simply a collection of revelatory solos but a treatise on the fundamental nature of ecstasy and despair. The gallows humor of Runnin’ with the Devil, the desperate yearning of Ain’t Talkin’ ‘Bout Love, the mad revelry of Jamie’s Cryin’—this album is an exploration of man’s folly, his insatiable desire, and his inevitable suffering. Even in its lesser-known passages—Feel Your Love Tonight, I’m the One, Little Dreamer—there is a hunger, a drive, a fire that refuses to be extinguished.

II. Women and Children First (1980)

The revelry continues, but here, it darkens. Women and Children First is a howl of defiance, a declaration that while the world may erode the spirit, one must still dance upon the ruins.

Songs such as And the Cradle Will Rock… and Everybody Wants Some!! present themselves as anthems for the damned, for those who see the world’s absurdity yet refuse to submit to despair. In Fools and Romeo Delight, Eddie’s guitar ceases to be an instrument and becomes an act of war, an assertion that to yield is to die. Meanwhile, Could This Be Magic? offers a moment of surreal, almost cynical reprieve, as if to mock the very notion of sincerity in a world so bent on deception.

III. Van Halen II (1979)

But there is always a moment when the condemned man forgets his chains, when the prisoner laughs despite his suffering. Van Halen II is such a moment—a reprieve, a seduction, a fleeting indulgence in the illusion of happiness.

Dance the Night Away is hedonism in its purest form, an invitation to cast aside burdens and simply be. Beautiful Girls is not a love song but an exultation of beauty, of pleasure, of that which we know will not last but must be celebrated nonetheless. Even in Spanish Fly, an acoustic marvel, we hear not just skill, but delight—as if Eddie, for a moment, has allowed himself to exist outside the pressures of greatness and simply play.

IV. Fair Warning (1981)

It was inevitable. No laughter lasts forever. No light can burn without casting shadows. And so we come to Fair Warning, the sound of revelry curdling into regret.

From the opening of Mean Street, we hear not the triumphant strut of the gambler, but the weary gait of the man who has lost it all. Unchained, for all its defiant energy, is no longer the voice of the carefree youth—it is the voice of the man who fights because he must, who rages because surrender is unthinkable. The beauty of Push Comes to Shove is not in its melody but in its melancholy—a slow, creeping awareness that the dance is nearing its end.

This is a great album, but it is not a happy one. And it should not be.

V. 1984 (1984)

And now the great turning. 1984 is not merely a shift in sound, but in philosophy. The synthesizers, the sleek production, the blinding neon of Jump—this is not rebellion, but assimilation. The wild creature of Van Halen has been put in a cage, and given a treat.

It is not without its virtues. Panama and Hot for Teacher still pulse with the old spirit. Eddie’s solos remain untouched by time. But something has been lost here. Or rather, something has been willingly given up. The freedom that once defined Van Halen has now been sold, traded for a throne in a kingdom of illusions.

VI. Diver Down (1982)

Finally, we arrive at Diver Down, the album that smiles even as it bleeds. It is, in many ways, a jest—a record filled with covers, diversions, distractions. Even its best moments—Little Guitars, Secrets—feel as if they are spoken by a man who does not wish to speak of his suffering, who would rather entertain than confess.

But even here, in this playful deceit, we find truth. Big Bad Bill (Is Sweet William Now) is a moment of warmth, an acknowledgment that even the wildest of men may one day long for quiet. It is a farewell to something—not just to a certain sound, but to an era.

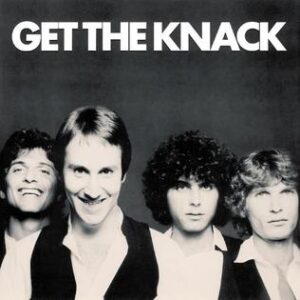

What is youth but the delirium of dreams, the reckless fumble toward ecstasy before the world crushes you into submission? Get the Knack is precisely such a delirium—brash and unrepentant in its yearning for something beyond itself.

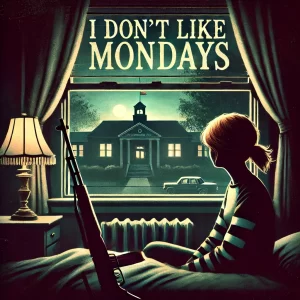

What is youth but the delirium of dreams, the reckless fumble toward ecstasy before the world crushes you into submission? Get the Knack is precisely such a delirium—brash and unrepentant in its yearning for something beyond itself. The morning began like any other in the quiet suburb, the sun rising reluctantly. Brenda Ann Spencer, a 16-year-old girl with flaming red hair and haunted blue eyes, woke up in her small room. The gun leaned against the wall, a stark reminder of a gift from her father — a gift that spoke more of neglect and misunderstanding than affection. The same gun that, in just a few short hours, would carve her name into infamy.

The morning began like any other in the quiet suburb, the sun rising reluctantly. Brenda Ann Spencer, a 16-year-old girl with flaming red hair and haunted blue eyes, woke up in her small room. The gun leaned against the wall, a stark reminder of a gift from her father — a gift that spoke more of neglect and misunderstanding than affection. The same gun that, in just a few short hours, would carve her name into infamy. There are certain creatures who, through the force of their will, or through some inexplicable fate, ascend to the throne of pop culture. One such creature is Taylor Swift, a woman whose sentiment has yielded a kingdom of devoted listeners. She, an empress of song, each note carefully positioned, each lyric smoothed to a palatable glow. Her music, rich in universal emotion, is a cathedral in which millions gather.

There are certain creatures who, through the force of their will, or through some inexplicable fate, ascend to the throne of pop culture. One such creature is Taylor Swift, a woman whose sentiment has yielded a kingdom of devoted listeners. She, an empress of song, each note carefully positioned, each lyric smoothed to a palatable glow. Her music, rich in universal emotion, is a cathedral in which millions gather.